|

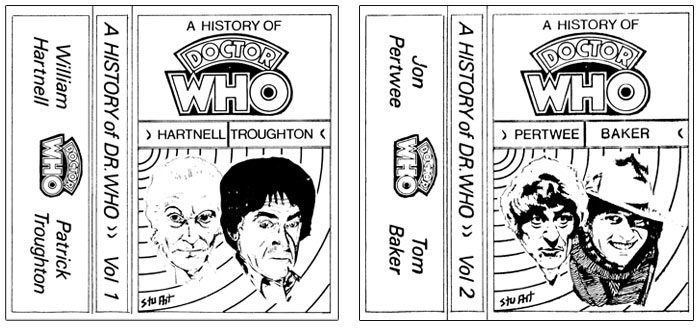

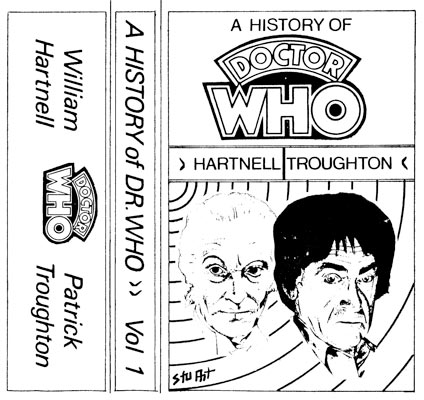

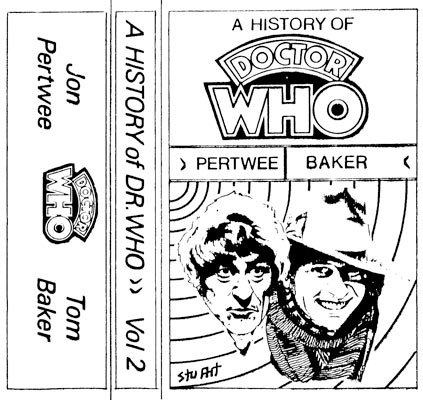

Images © Stuart Glazebrook, 1977

|

Basic Information |

|

Place of Origin:

Hendon, London, UK

Editors:

J. Jeremy Bentham and Gordon Blows

In

Production:

1976-77 |

Distribution Media (Limited Release):

Audio Cassette

Tape Lengths:

#1-2: C-90

Issues Produced:

2 |

“Can you imagine silver leaves waving above

a pond of liquid gold containing singing fishes?

Twin suns that arc and fall in a rainbow heaven.

Another world in another sky…

If you would come with me, I will show you all this –

and it will be, I promise you, the dullest part of it all.

Or stay behind and regret your staying until the day you die.”

Attributed to David Whitaker, this quote

featured in

the introduction to A History of Dr. Who

While not strictly a tapezine itself, more an audio

documentary, J. Jeremy Bentham and Gordon Blows’ A History of Dr. Who

was under starter’s orders some seven years before the first true

tapezine surfaced. A relic from the early days of fandom, the three-hour

audio programme was devised as a way of telling the story of the first

thirteen years of Doctor Who through audio clips from the

television stories interspersed with informed commentary to link them.

“The idea to do the Doctor Who History Tapes

came right at the beginning of the Doctor Who Appreciation Society

(DWAS),” recalled Bentham when interviewed by Alan Hayes in October

2007. “At that time, the only people that I knew who had tapes of

anything significantly pre-Pertwee were Jan Vincent-Rudzki and Richard

Landen. Back in those days, with the available technology, making copies

was a lengthy, real-time process because it involved physically going to

see to see somebody, usually armed with sets of leads, your own tape

recorder or, at best, a compact cassette deck – even cassettes were

still fairly new in 1976. So, it was always a question of when you could

get together and for how long to make a copy of this tape or that tape.

Geographically, Jan was closer and had a few very early recordings, such

as the first episodes of The Daleks – complete with motorbike in

the background at one point – but ones we used from The Daleks’

Master Plan onwards were mostly Richard’s. The problem with Richard

was that, at the time, he lived down in Warminster in Wiltshire, so

going to see him was one of those occasional experiences when you had

enough money to pay for a train fare or, from 1977 onwards in my case,

the petrol to drive down. A lot of the original DWAS organising

committee didn’t have driving licenses when the society first began! The

soundtrack clips used for the 1970s sections were generally from my own

recordings, which had kicked in by then.”

The choice of clips was limited by what the

producers had available to them at the time. From a modern perspective,

when all episodes of the series are easily available in restored form on

physical media, streaming sites or spoken word compact disc releases,

this in itself is one of the fascinations of these tapes. These often

indistinct recordings, complete with buzz and hum, are exactly what many

Doctor Who fans grew up listening to. In an era when the BBC

Audio Doctor Who soundtrack range was a fan’s impossible pipe

dream, and before the high quality treasure troves of sound recordists

such as Graham Strong and David Butler came to light, these cassettes

were a godsend to Doctor Who fans desperate to hear excerpts of

old stories that were otherwise lost in the mists of time. Fans who have

come to the series over the last thirty years are unlikely to have

experienced the excitement of getting their hands on a dodgy, barely

audible soundtrack of a long-lost Doctor Who story, and as such,

A History of Dr. Who is something of a time capsule, which, as a

document of a series with the concept of time travel at its centre, is

wholly appropriate.

“When the Appreciation Society started in May 1976,

there were very few ‘source’ recordings from which duplicates had been

made,” remarked Jeremy when asked about the availability of recordings.

“Additionally, we were a little bit hamstrung by the technical quality

of our own recordings. Although I later acquired a DIN lead [an

electrical audio connector that was standardised by the Deutsches

Institut für Normung, the German Institute for Standards, in the early

1970s] connected directly to the television, in the early days, many of

my contemporaries and I were simply plonking microphones in front of TV

loudspeakers, hoping desperately not to get any levels of hum or buzz.

You never knew until you played it back afterwards as to whether you had

been successful or not!”

A History of Dr. Who was presented across

two audio cassettes, with the first devoted to William Hartnell and

Patrick Troughton’s eras, while the second focused on those of Jon

Pertwee and Tom Baker. Jeremy and Gordon produced the programmes on a

4-track open reel 1/4” tape recorder in 1976, with the compact cassette

the planned delivery medium.

“The initial idea of doing the History tapes

stemmed from my desire to do something to substantiate the output from

the Reference Department, which was my little end of the empire,”

comments Jeremy. “At that time, the rather bad photocopies of typed

two-page, cast list synopses and very few – maybe half a dozen –

slightly more substantial plot breakdowns were all that constituted what

I could bring to the party. We considered what else we could offer to

members of the Society and an idea that emerged between the Publications

head, Gordon Blows, and myself was possibly to do an audio ‘potted

history’ of the programme that we could duplicate and send out on a

cassette.

© Who's Listening

“When we started mapping the audio history project,

it became apparent that it wasn’t going to fit onto one nice, little

C-60 cassette. We had initially thought of putting William Hartnell and

Patrick Troughton on one side, and Jon Pertwee and Tom Baker on the

other, but we quickly realised that even if you included just half a

dozen soundtrack clips, you’d almost need one side per Doctor – and more

likely one half of a C-90 to do justice to each. So the tapes really

evolved as they went along, but we did start with a script. I started

out with an A3 sheet of paper and drew a line down the middle of it. On

the right-hand side, I annotated the clips we wanted to use: the best

bits from the recordings we had access to, with approximate timings,

while on the left I added the bits of linking narration that Gordon or

myself would do. If there was something else that needed to be covered,

like a sound effect or a piece of mood music, or something like that, we

scribbled that down the middle of the page, saying something like

‘bridge fade in to Genesis of the Daleks with cymbal crash from

Days of Future Passed (The Moody Blues)’.

“We were, of course, limited by the soundtrack

recordings we had available to use. With the Tom Baker one, we were

aware that there wasn’t really much material of his to work from [as the

planning of A History of Doctor Who came at a time when only two

full seasons of Tom Baker stories had been transmitted]. Genesis of

the Daleks became such a big feature of his side because we realised

it was one of the key stories that had ever been done for the series. We

were looking for topics that were of significance in the development of

Doctor Who rather than just ‘another good Cybermen clip’, and

this meant that some other stories did not meet our criteria as readily.

“If I remember rightly, we approached the

production process in almost the reverse order, starting with Pertwee

because we had the most quality recordings from that period, with the

Hartnell and Troughton sides done last, as we were always waiting for an

opportunity to see Jan or Richard to blag another couple of episodes

from them. I know I wanted to include an extract from The Macra

Terror but we literally ran out of time.

“In terms of script and running order writing, I

did most of it, from facts that were known at the time, drawn largely

from the background history that Jan and Stephen Payne had researched

and written documenting how the show had come together at the beginning.

Then, having blocked it out, I realised I needed another voice-over and

Gordon was the one who was up for supplying it. We tried to work out

whether we could approach it with the first person dealing with the

narrative history of Doctor Who – the fictional context of the

programme and what we had learnt about the Doctor – and the other person

doing the technical commentary, the behind-the-scenes stuff, which is

sort of how it panned out. Gordon covered the biographies of the main

characters and explained what was happening in television land, while I

looked at it from the angle of what we had discovered about the Doctor

and other characters since 1963. That seemed like an equitable division

of labour, bearing in mind that Gordon was the publications editor of

TARDIS and I was the one who people would write to at the Reference

Department if they wanted to know how many times the Doctor had said,

‘reverse the polarity’ or something similar. That seemed to work as a

concept idea, but I’m sure that because we needed to worry about little

filler pieces, it wasn’t completely consistent all the way through.”

The recording sessions were simply a case of

cross-taping the elements in sequential order and working out a rough

time schedule, which was accomplished largely by Jeremy pacing up and

down with a stopwatch, reading the text at his natural delivery speed

and tailoring the script accordingly if something seemed too short or

too long… “All with the abiding thought that you can’t get much more

than 45 minutes onto one side of a cassette. It was all very

unsophisticated!” Jeremy admits.

“We captured the master recordings onto a Ferguson

3248 Auto-recorder, a four track, stereo open-reel tape recorder that

was capable of running at two speeds – 1⅞ or 3¾ inches per second – and

you’d try to record at as high a speed as you could, to get the best

quality,” Jeremy notes. “We’d eventually dump the recordings down to a

slower speed when we were trying to squeeze everything on to an 1800

foot reel. Occasionally, I’d use a cassette recorder to real-time feed

in underlying sound effects or music tracks via a very basic mixing

box-type thing. For example, with Track A largely reserved for clips,

and Track B largely reserved for narration, anything else had to be

merged in during the compilation of a Track A or B master recording.

We’d try to do these tricks as seamlessly as possible in one take, but

if something went wrong, we had to virtually knock out that entire

recording and start the whole track again, working out the fade segues –

the point where we’d, say, fade from Track A into Track B before going

back to Track A again. That’s why it took so long. By today’s standards,

it was incredibly crude.

“As mentioned before, one aspect where we found

ourselves experimenting was in the use of music and effects to try and

instill a sense of awe throughout the whole production. Doctor Who

had, after all, been on air for thirteen years, so it was worthy of some

kind of reverential treatment. We tried several different ways of doing

audio effects as I’d long been a fan of BBC radio dramas and had often

thought, ‘Wow! That’s spooky the way they’ve used eerie background music

or subtle vocal treatments to create a sense of atmosphere’. We simply

tried to emulate some of that within the technical constraints of what

we had to hand at the time. We ended up using music from bands like Pink

Floyd – interestingly before one identical track appeared in an early

dub of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. I employed a variety

of very basic techniques, including putting microphones into baths to

give us some sense of reverberation and creating odd effects by parallel

recording the same speeches onto two tracks; one track would be captured

at regular speed and the second captured with a weight on one of the

spools, just to cause a slight artificial slowing down of that second

track. That way you could either bring the track up to sync to fade out

the echo or introduce it when you wanted to put it back on. We also

created a Cybermen voice for the Troughton history by placing the

microphone in, I think, some sort of metal cannister resting on a metal

surface to give the voice a tinnier edge. I recall it was done with the

intention of trying to impersonate Christopher Robbie’s voice from

Revenge of the Cybermen. I would also have tweaked the treble and

the bass controls on the recorder to boost the effect, but there was

never anything sophisticated enough even to try and do any form of basic

ring modulation. I just didn’t know how to do it!”

However, while production was underway, a change in the nature of the DWAS in late 1976 caused a

sudden and complete rethink regarding the intended distribution of A

History of Dr. Who to society members, as Jeremy Bentham relates:

“Up until mid-1976, membership of the national Appreciation Society

wasn’t really much larger than that of the original society at Westfield

College, Hampstead, where between 30 and 40 students would regularly

turn up in the common room and watch Doctor Who on a Saturday.

When we were about halfway through compiling the History Tapes, the

membership levels of the DWAS got significantly boosted when producer

Philip Hinchcliffe kindly put a reference to the Appreciation Society in

the Radio Times feature advertising The Masque of Mandragora.

Suddenly, membership numbers began to swell significantly, and with the

on-going absorption of membership from Brian Smith’s former Doctor Who

International Fan Club, they rose to over 400 people on the registration

lists by the end of September 1976.

“Grim realisation steadily dawned that A History

of Dr. Who wasn’t going to be feasible to do as a product that we

could generally advertise and send out to the membership. The naïvety of

it all was quoshed by the scale of how long it would take us to do such

a large number of duplicates. None of us had any access to any form of

sophisticated bulk duplication facilities and soon realised that it was

going to become a real problem to do many copies, because they all had

to be done in real-time.

“Eventually it was decided to award the History

Tapes as a prize in one of the early competitions run in TARDIS, the

features ’zine of the Society, though even then we had to state ‘when

they’re ready’ as we didn’t finish them until early 1977.

“The version given in the competition to prize

winner, Anne Micklethwaite, was unique in that, at the stage where we

came to send it out, I didn’t have a recording from either of the two

stories that featured the Ice Warriors for the Troughton section. I had

to do a cheat, and lift a track from The Monster of Peladon, just

so there was an Ice Warrior example on the tape. Later, after another

trip to see Richard Landen, and having come back with a copy of The

Ice Warriors, we were able to overdub a more appropriate excerpt

over that original recording. If you listen to the Troughton side,

there’s almost an audible click where the clip from The Ice Warriors

was dropped in, and as we were constrained by the duration of the

previous clip already on the master tape, you can hear it terminate

suddenly in a place that wasn’t really the best from an artistic point

of view to end the sequence.

“Although we probably should have sought BBC

approval to produce and issue the tapes, in those days we were very much

‘flying by the seat of the pants’, hurtling into the unknown with very

little idea of where we were going and how we were going to get there.

Once we began forming stronger links with the likes of Philip

Hinchcliffe and Robert Holmes, we started picking up on what we were

allowed to do and what we weren’t allowed to do. Again, this was part

and parcel of scuppering the idea of A History of Dr. Who ever

becoming a product that we were even tacitly going to be allowed to do –

even if we never intended to make money from it.

“As it was, when people started asking for copies

of these tapes, as they began hearing about them once the news spread,

if ever I did a copy for somebody, I always used to send along a little

multi-part form, that had to be signed and sent back to me, stating that

the recipient agreed these recordings would be used for private research

purposes only and not for any form of commercial distribution. This was,

more than anything, to cover ourselves against people thinking we were

doing it all for profit, and thereby cheating writers, production people

and performers out of royalties. Such duplicates were never done with

any great knowledge at the time of the intricacies of copyright and all

the permissions you’d need to do it even for an amateur product done

through a private society.”

In addition to the writing, recording and editing

required to realise this project, Jeremy had considered in the early

stages the visual presentation of the cassettes and had contacted Stuart

Glazebrook, a graphic designer and artist who lived in Atherton,

Manchester, and whose artwork adorned many DWAS publications in the

Society’s early days. “As well as being a talented illustrator, Stuart

was ideally placed to run the DWAS Art Department because he had the

good fortune to work for a design and print company. Via a combination

of his own skills and some ‘Letraset’ rub-down lettering, he fashioned

the two cover art templates and sent them to me as heavy-weight paper

galley proofs. Anne Micklethwaite’s cassettes were sent to her with

carefully sliced up galley proof covers. For everyone else it was more

expedient to photocopy the other galley sheets and slice the covers to

shape with a scalpel and cutting board.”

Unofficial CD cover

Image © Who's Listening / Stuart

Glazebrook, 2007

A History of Dr. Who covered the period from

the first Doctor Who story, An Unearthly Child, up to the

final story of Tom Baker’s second season as the Doctor, The Seeds of

Doom. Jeremy Bentham reveals that there was some thought given to a

possible continuation of the project. “We did consider adding updated

tracks for seasons that went beyond that. Some thought was also given to

possibly producing a supplemental tape, but by late 1977, the

Appreciation Society was getting to be a very demanding aspect of all

our lives and any free time to do it was becoming very constrained. So,

the will to continue was there, but never the mechanics or the resources

to actually realise it. Brian Hodgson was just never free when you

really wanted him!”

J. Jeremy Bentham, a co-founder of the

Doctor Who Appreciation Society, went on to join the staff of Marvel's

Doctor Who Weekly as principal writer and associate editor in

1979. The 'associate editor' job title was not entirely accurate in that

Jeremy was given a free hand by editors Dez Skinn and Paul Neary, and

wrote almost all the content. He moved on in 1982, by which time the

publication had become a monthly title. While working for Marvel, he

also co-founded Cyber Mark Services, an independent fan service

producing story-by-story reference magazines - initially An Adventure

in Space and Time (1980-1985) and then rebranded from Robot onwards

as In-Vision (1985-2003). He also wrote Doctor Who: The Early

Years (W.H. Allen, 1986), a groundbreaking reference work looking at

the creation and early days of the series. He also served as

co-organiser of the British Film Institute's Doctor Who - The

Developing Art weekend at London's National Film Theatre (now the

BFI Southbank), celebrating the programme's twentieth anniversary.

In terms of content and presentation, the four

sections of A History of Dr. Who were well planned and

constructed, dealing with the eras thematically rather than in a

story-by-story, linear fashion. Narration was of a high standard, and

well-written, quite often having a magic all of its own when combined

with the progressive rock backing tracks.

Despite the ‘Heath Robinson’ techniques applied to

compensate for the dearth of audio technology available to the

producers, the sound design on these tapes is surprisingly good and

often highly inventive, with the various experimental sound effects

working exceptionally well more often than not. For a multi-generational

domestic production of the era it has the wow factor.

Considering the limitations under which J. Jeremy

Bentham and Gordon Blows were working, A History of Dr. Who

represents an outstanding achievement – and one that also stands as a

fascinating snapshot of early fandom and as an analysis of the series at

a point halfway through its original run.

Alan Hayes

Note: The William Hartnell era story titles given

are those used on the cassettes as they had not been formalised by the

time A History of Dr. Who was recorded.

A HISTORY OF DR. WHO – VOL. 1: HARTNELL / TROUGHTON

1976-1977, C-90

Side A:

-

Introduction by J. Jeremy Bentham and

Gordon Blows

-

An Unearthly Child – A legend begins

-

The Dead Planet – The greatest menace of all

-

Invasion Earth 2164 A.D. – The Doctor’s Character

-

The Chase – Ian and Barbara’s departure / Daleks and

Mechonoids / Stephen Taylor

-

The Myth Makers and other historical stories

-

The War of God – Unexpected destinations

-

The Dalek Masterplan – The death of Katarina / TARDIS

lands at the Oval

-

The Dalek Masterplan – The Doctor’s pride in his Ship

-

The Dalek Masterplan – The Meddling Monk, one of the

Doctor’s race

-

The Celestial Toymaker – The Doctor Who magic

-

The Chase / The Ark / Dr. Who and the Daleks

/ The Dalek Masterplan /

Invasion Earth 2164 A.D. / The Chase / The Dead Planet

– The Monsters

-

The Tenth Planet – The Cybermen / Change is imminent

Side B:

-

The Tenth Planet – “It’s far from

being all over!”

-

The Power of the Daleks – “I’ve been renewed!”

-

The Moonbase – The Doctor’s uniquely aggravating

manner

-

The Highlanders – Jamie McCrimmon comes on board

-

Fury from the Deep – The TARDIS lands on the sea

-

The Evil of the Daleks – The Emperor Dalek / Victoria

Waterfield

-

The Web of Fear – The Great Intelligence / Colonel

Lethbridge-Stewart

-

The Tomb of the Cybermen – The Cyber Theme

-

The Tomb of the Cybermen – The Cybermen’s superior

trap

-

The Seeds of Death – The Ice Warriors (*)

-

The War Games – The Time Lords / The Doctor’s Trial

(*) A recording of The Seeds of Death was unavailable when A

History of Doctor Who was awarded as a competition prize. In that

original version, an excerpt from the Jon Pertwee story The Monster

of Peladon appeared in its place.

A HISTORY OF DR. WHO – VOL. 2: PERTWEE / BAKER

1976-1977, C-90

Side A:

-

The War Games – The end of an era

-

Spearhead from Space – A new, dynamic Doctor / Dr.

Elizabeth Shaw

-

Spearhead from Space – The Doctor and the Brigadier

discuss terms

-

The Dæmons – Sergeant Benton rescues Miss Hawthorne

-

The Green Death – Captain Yates infiltrates Global

Chemicals

-

Terror of the Autons – The Doctor and Jo get off on

the wrong foot

-

The Green Death – Jo leaves the Doctor’s side

-

The Time Monster / Frontier in Space – The

Master

-

The Time Monster – Bessie

-

The Dæmons / The Curse of Peladon / The Sea

Devils / The Three Doctors / Planet of the

Daleks / The Time Warrior / Planet of the Spiders /

Day of the Daleks – The Monsters

-

The Time Monster – The Doctor Who magic

-

The Three Doctors – The Doctor’s freedom is returned

to him

-

Planet of the Spiders – “Give me the crystal. I search

for it. I ache for it!”

Side B:

-

Planet of the Spiders – “I had to

face my fear, Sarah”

-

Robot – A new face, a very different new Doctor

-

The Ark in Space – The Doctor’s keen mind at work on

Space Station Nerva

-

Robot – Sarah Jane Smith investigates Think Tank

-

Terror of the Zygons – Harry Sullivan

-

Genesis of the Daleks – The origins of the Daleks

-

The Brain of Morbius – A Time Lord criminal deepens

the myth

-

The Seeds of Doom – The Doctor grows more distant and

dispassionate

-

Pyramids of Mars – The Doctor reflects on his place in

the Universe

-

Robot / The Ark in Space / The Seeds of Doom

/ Pyramids of Mars / The Dalek Masterplan / The Power

of the Daleks / Day of the Daleks / Genesis of the Daleks

– The Monsters

-

Looking ahead to Season 14 and the Doctor Who Feature

Film

-

A History of Dr. Who – Sign Off

|